AofA's Hot To Trot Talking Points

Every Friday

Such an important topic and so glad that Prue Leith is able to speak out about it. Her brother died in pain of cancer and she is determined not to have the same experience. Good on her. I wouldn’t call it suicide myself and that is probably the Telegraph, but I think it’s a good idea to think about how we can effectively end our lives in a pain-free way if assisted dying is not legalised.

Exercise, of course, is a thing as we get older. And so I asked our community how they were doing? I feel best when I’m playing tennis three times a week, and I try to do a 15 min routine with a kettle bell, shoulder stands, stretches, standing on one leg etc every day. And the University of Birmingham are researching -

‘Fewer than 35% of older adults in England achieve recommended activity levels - even though staying active is one of the most effective ways to reduce age‑related cognitive decline.

To change that, Dr Katrien Segaert and Professor Sam Lucas have been awarded £1.9 million in funding to pinpoint the optimal exercise intensity needed to boost cognitive function and increase blood flow to the brain in later life.

Too little activity may offer no cognitive benefit, while pushing too hard can raise the risk of injury, fatigue, and falling motivation. Identifying the “just right” level of exercise is essential for safe, sustainable brain‑health outcomes.

Working in partnership with Age UK Birmingham and local older adults, the team will co‑produce evidence that could shape clear practical guidance that helps people stay active in ways that genuinely support healthy ageing.’

Find out more: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/.../how-hard-do-you-actually...

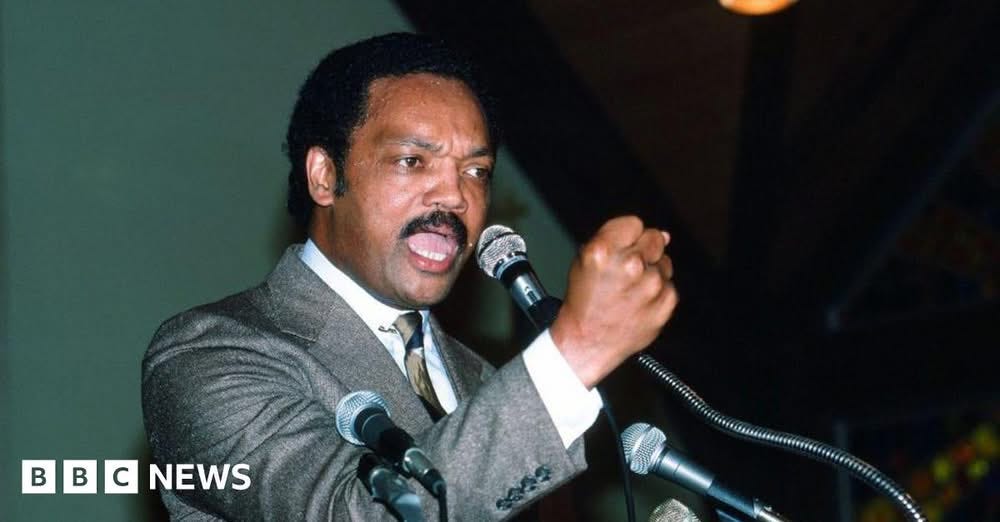

Sad to hear that activist, Jesse Jackson has died at the age of 84. Funnily enough, I was in the stylish clothes shop Avant Garde with a friend last week as sadly it's closing down. Harlesden's Gorgeous George - George Dyer, 76 - the owner was there. And there was a photo of Jesse Jackson visiting the shop in the 80s!

Photo from the Guardian. One of our members reminded me of this remarkable woman, Hannah Hauxwell. We were inspired again by her story.

In 1972, a film crew found a woman living alone on a mountain farm with no electricity, no water, and no one who knew she existed. She’d been there for eleven years. She was 46 — but looked decades older.

Her name was Hannah Hauxwell.

She lived at Low Birk Hatt Farm — an 80-acre stone smallholding in Baldersdale, deep in the Pennine hills of northern England. One of the most remote, wind-battered, unforgiving places in the country.

No electricity. No running water. No telephone. No central heating. No indoor plumbing. Her water came from a stream two hundred yards away, carried in buckets. Her light came from oil lamps. Her heat came from a coal range.

She slept in an old army greatcoat to survive the winters.

Her entire income came from selling one cow each year at Barnard Castle market — roughly £250 to £280. At the time, the average salary in Britain was over £1,300. Hannah survived on less than a fifth of what most people earned.

Her diet was porridge, bread, and tea. Her bath was a cow pail. Her bread was delivered to a gate three fields away, and she walked through whatever weather awaited her to collect it.

And she had been living this way — completely alone — since 1961.

Hannah was born on August 1, 1926, in Baldersdale. Her parents, William and Lydia, bought Low Birk Hatt when she was three. But her father died when Hannah was just six years old, and her Uncle Tommy took over the running of the farm.

Hannah attended the local school until she was 14, then joined the family work. She never left.

When her mother died, followed by her uncle three years later, Hannah was 34 years old — unmarried, alone, and responsible for an isolated hill farm that barely produced enough to survive on.

She had no money to leave. No skills beyond farming. No connections outside the dale. So she stayed. And she worked. Year after year after year.

In summer 1972, a friend of a researcher at Yorkshire Television happened to encounter Hannah while walking in the Dales. Word reached producer Barry Cockcroft. He went to find her.

What he found stunned him.

A woman living in conditions that Britain assumed had vanished with the Victorian era — still existing, in total isolation, in 1972.

Cockcroft made a documentary. He called it Too Long a Winter.

It aired in early 1973. Britain’s heart broke.

Viewers watched Hannah lead a cow through a blizzard in ragged clothing. They watched her break ice in water buckets. They heard her quiet, matter-of-fact voice describe her life without a trace of self-pity.

“In summer I live,” she said. “And in winter I exist.”

When asked what kept her going, she spoke about the view from her kitchen — the rolling dale stretching out beyond the iron gate. “It’s one thing — if I haven’t money in my pocket, it’s one thing nobody can rob me of.”

Yorkshire Television’s phone lines were jammed for three days.

Hundreds of phone calls. Thousands of letters. Gifts, money, warm clothing from strangers who couldn’t believe such poverty still existed in modern Britain. A local factory raised money to connect Low Birk Hatt to the electrical grid.

At age 46, Hannah Hauxwell saw electric light in her own home for the first time.

She was invited as a guest of honour to the Women of the Year gala at the London Savoy Hotel, where she met the Duchess of Gloucester. This woman who’d barely left her dale was suddenly standing in one of the most famous ballrooms in England.

But the farm was still there. The winters were still brutal. And Hannah was getting older.

By the late 1980s, her health was failing. The sub-zero winters she’d endured for decades were becoming impossible. In December 1988, at age 62, Hannah made the heartbreaking decision to sell Low Birk Hatt Farm.

“A big part of me, wherever I am, will be left here,” she said.

The documentary crew returned one final time to film A Winter Too Many. It ended with Hannah and her remaining possessions leaving the farm in a removal lorry, towed by a tractor as the snow fell again.

She moved to a small cottage in the village of Cotherstone — five miles from the farm. It had central heating. Running water. An indoor bathroom.

Hannah admitted she was delighted with the bathroom. But she also confessed she never used the washing machine.

Some habits from a lifetime of self-reliance don’t break easily.

Then something extraordinary happened. The woman who’d barely left her valley in 62 years began to travel.

In 1992, at age 65, Hannah Hauxwell left Britain for the first time. Cockcroft filmed her grand tour of Europe — France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.

In Rome, she met the Pope.

The series was so popular that the following year, she traveled to America, filmed as Hannah: USA. In New York, she reportedly observed: “I thought they would be more civilised and know how to make tea properly.”

Meanwhile, the farm she’d left behind produced one final gift.

Because Hannah had never used modern pesticides, never re-seeded her fields, and never applied artificial fertilizers, her meadows had quietly become one of the best-preserved wildflower habitats in the Pennines. Rare species flourished in the soil she’d worked by hand for decades.

Her land was designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It was renamed Hannah’s Meadows, and is now managed by the Durham Wildlife Trust.

Her poverty had accidentally created an ecological treasure.

Hannah spent her later years in Cotherstone, living frugally — still mending her clothes by hand, still repairing her mattress rather than buying a new one, still listening to the news on the radio and talking passionately about world events.

She moved to a care home in Barnard Castle in 2016, and to a nursing home in West Auckland in 2017.

Hannah Hauxwell died on January 30, 2018. She was 91.

She was buried at Romaldkirk Cemetery, not far from Low Birk Hatt. Her gravestone is a modest boulder with a carved face looking out toward the Dales — often adorned with flowers from people who never met her but never forgot her.

Hannah didn’t choose her life. She inherited it. She endured it because there was no alternative. And when the world finally found her, she accepted help with quiet grace — but never pretended it had been anything other than what it was.

Hard. Lonely. And somehow, still beautiful.

“It’s one thing nobody can rob me of,” she said about her view from the kitchen window.

The view is still there.

And so is Hannah’s story — reminding us that dignity needs nothing but itself.’’

5. We continue to admire Tracey Emin not only for her frankness - and the end of that quote is a bit iffy really. As one of our members pointed out - actually the one who shared it - it’s not the central point of the piece. Anyway Tracey, as we know had some major health events that could have killed her, her health still makes huge demands on her and she’s still living life to the absolute hilt!!

We loved this top! In theory. Although we realise the reality is itchy. The Tattie Sack top. Go Bromley go. One of our members mentioned that Marilyn Monroe wore a hessian dress at one point and she did.

‘A Cornish farmer believes he may have accidentally invented the next big fashion trend after turning old tattie sacks into summer clothing.

Bromley Trevaskis, 74, from a farm near Hayle, said the relentless rain had forced him to “think outside the tractor”.

“The weather’s ruined half the year,” Bromley explained. “So I thought I’d diversify.”

Using hessian sacks that have been sat in his barn for over 30 years, Bromley has cut holes for the head and arms to create what he describes as the “Tattie Top”.

Although he hasn’t sold a single one yet, Bromley is confident demand will soar once holidaymakers catch wind of it.

“Especially the rich ones” he said. “They love anything real Cornish. It’s vintage, all natural material, breathable and limited edition. At just fifty quid each, I reckon they’ll be fighting over them.”

He added that once the sun finally comes out, his ‘tattie top’ would be “ideal for beach walks, food festivals and standing outside cafés in St Ives trying to look cool.”

One local who briefly tried one on said it was “surprisingly airy” but admitted it was “a bit itchy on the nips.”

Bromley says he’s now considering a winter range, “just two sacks sewn together.”’

Totally in agreement with Prue - and I wouldn't call it suicide either. I always talk about 'taking one's own life'. A much gentler expression, and seems to me reflects some people's wishes as they grow older and have had enough of whatever it is, be it just living, or their illness.

Definitely recommend Tim Ferris's book The 4-Hour Body. One section is the most efficient thing to do - it involved kettle ball - to keep in shape with least time spent. Not addressing cognitive in that part, but still with the read.